Living the high-flying life with a humble heart and humble start

USAF Captain George J. Marrett is an award-winning test pilot, Vietnam veteran, U.S. Air Force officer, museum co-founder, successful author, film consultant and public speaker. In so-called retirement, he continues to honor our soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice in service of the United States.

In 1941, six-year-old George stands with his friend in Grand Island, Nebraska wearing flight goggles and a leather helmet.

In 1941, six-year-old George loved listening to the sounds of airplanes. His cherubic face looked upward, squinting in the sun at the approach of B-17s. The winged beasts roared passed, casting shadows over flat terrain in Grand Island, Nebraska. It was within this farming and railroad community that the boy – wearing flight goggles and a leather helmet as he daydreamed – wanted so badly to be a pilot.

At 18, the lanky Eagle Scout joined the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) at Iowa State University. Marrett became commissioned as a Second Lieutenant upon graduation. It was settled. There would be no other direction to go but up, and up he climbed.

Tests of speed and stealth

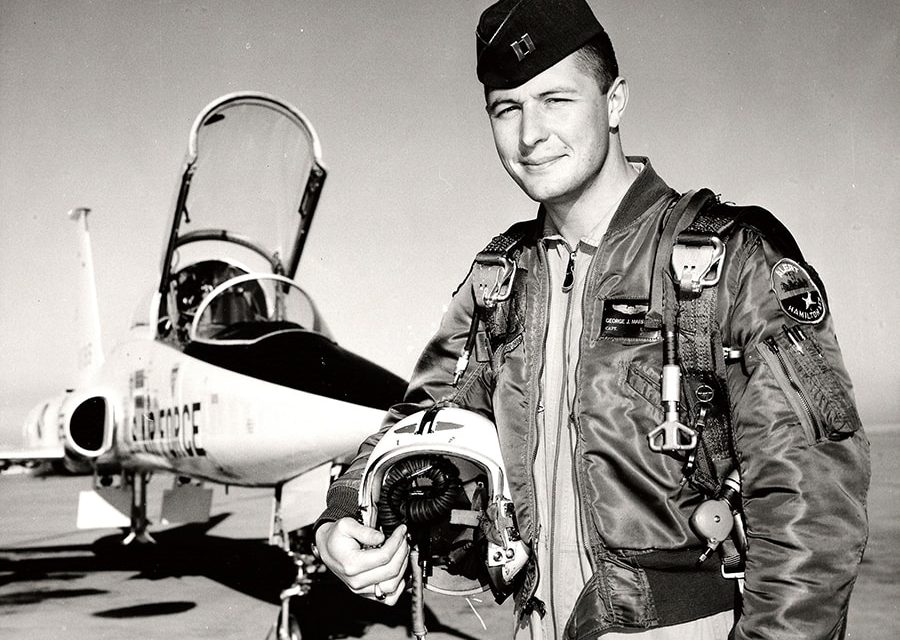

George Marrett with the F-104A Starfighter.

In Advanced Training, Marrett flew the radar-equipped F-86L “Sabre Dog” at Moody Air Force Base, Georgia. At age 24, the First Lieutenant joined the 84th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Hamilton AFB in Novato, California. He flew the low-altitude F-101B Voodoo, and during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis defended the Golden Gate Bridge on our Western border.

With 1,500 hours in the air recorded, Marrett entered the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School, followed by Flight Test Operations at Edwards Air Force Base. As a test pilot, exponential physical and mental demands coupled with flying prowess catapulted him to another level.

For Marrett, his was an era of aeronautical and record-breaking wonders – and he did each aircraft justice. They included the world’s first supersonic trainer – the T-38 Talon, the F-104 Starfighter – engineered to fly twice the speed of sound, the F-106 Delta Dart, the Mach 2.2-capable F-4C Phantom, the F-5A Freedom Fighter and the swing-winged, penetrating F-111 Aardvark.

Waves of war in Southeast Asia

The launch of the 1968 Tet Offensive escalated urban warfare throughout South Vietnam, where highly organized attacks stunned and decimated the region. In Thailand, Marrett served as a combat search and rescue pilot with the 602d Air Commando Squadron at the Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base and Nakhon Phanom Royal Navy Base. He flew the A-1J Skyraider, a single-engine, low-and-slow flying workhorse developed during World War II, and altered the Laugh-In TV show motto into a deadly serious “Sock It To ‘Em.”

Merrett’s Distinguished Flying Cross.

In 1968, Marrett fought through hot-zones of heavy warfare in Vietnam and Laos. If enemy fire and surface-to-air missiles didn’t end you, monsoons very well could. Marrett and fellow pilots sortied again and again to loiter low in grueling searches of downed soldiers. His bravery yielded three commendations – the Distinguished Flying Cross with two Oak Leaf Clusters, Air Medal with eight Oak Leaf Clusters and the Air Force Commendation Medal.

Safely home, Marrett became a test pilot for Hughes Aircraft Company. For two decades, his reconnaissance efforts partnered with the company’s attack radar and missile technology. His stable of fighters included the F-14 Tomcat, F-15 Eagle, F-16 Fighting Falcon, F-18 Hornet and an early prototype of the B-2 Stealth bomber. Marrett later provided television commentary about Howard Hughes for History Channel programs, as well as for “Making of The Aviator” and DVD commentary for the Martin Scorsese film, “The Aviator” (2004).

So-called retirement

Captain Marrett’s “retired” status looks anything but sedentary. He bikes regularly, exercises an encyclopedic memory in intricate detail, from military individuals to missions, and he is either in charge of various projects or lends energy in support of others’ efforts. Marrett speaks matter-of-factly of his accomplishments, but his awe of fellow colleagues and their collective feats of heroism is palpable. To that end, he and others established the Estrella Warbirds Museum (www.ewarbirds.org) – a 20-acre spread of artifacts, documents, wartime vehicles and aircraft, past and present.

Marrett’s authored four nonfiction books – “Cheating Death: Combat Air Rescues in Vietnam and Laos,” “Howard Hughes: Aviator,” “Testing Death: Hughes Aircraft Tests and Cold War Weaponry” and “Contrails Over the Mojave.” In 2016, Marrett was honored with the USAF Test Pilot School Distinguished Alumnus award at Edwards AFB.

Freedom Flight

Marrett’s air missions are far from over. In 1992, his close friend and World War II B-29 pilot, Obbie Atkinson, initiated the idea of providing military flyovers to honor deceased veterans. Along with Marrett, “Freedom Flight” was born. In his Aeronca L-16, Atkinson led the formation. Fittingly, Marrett reprised the “Sock It to ‘Em” moniker on his 1945 Stinson L-5E Sentinel.

“We flew a two-ship formation,” said Marrett. “I flew his right wing in my Sentinel and did the Missing Man formation pull-up.” However, tragedy struck in 2011 when Atkinson perished in a crash of his own plane. After delivering a speech in the museum hangar, Marrett honored Atkinson once more in the air, pulling up, then steering right and away as the missing man, “a very, very sad day.”

The formation is led these days by Scott Stelzle in his 1946 J-5 Cub, and Bob Kelley, who pilots a 1946 L-16 Aeronca on the left wing. On the right is Marrett, who continues to symbolize the missing man.

“The families of a departed one always tell me that, just as I make the Missing Man pull-up, they’re able to let their loved one go. That’s probably the hardest thing to do as a human,” said Marrett. “They are somebody’s husband or brother who didn’t make it back. We all feel like we lost someone in combat. Part of us leaves with them and vice versa.”

Marrett believes there is an intrinsic responsibility presented to those fortunate to live on. “What we do with our lives in light of their passing is representative of them. We can volunteer in our communities, help those who are homeless or care for children in some way,” he said. “These soldiers gave us their full measure – and we need to give ours, too.”